ii. What is Ecosystem Oriented Architecture?

What is Ecosystem Oriented Architecture?

Understanding ecosystem-oriented architecture requires one to fundamentally shift their thinking away from legacy information technology and software implementation practices. It is a shift that forces decision makers to fight their urge to resort to scattershot methods to resolve seemingly urgent problems, and instead keep a holistic view, forcing even the smallest changes into a repeatable pattern.

“Point solutions solve for a specific number of known things. An ecosystem solves for an infinite number of unknown things.”

So, ecosystem-oriented architecture is an architectural approach integrating technologies across an organization’s entire cloud estate, prizing flexibility, the adoption of new tech, and thoughtful application of the principles of EOA that we will discuss next.

Principles

Let’s begin with the core principles of EOA. Think of these principles as “lenses” through which ecosystem architects, technical leaders, and decision makers should consider their architectural choices and investments. In other words, the best ecosystem architects will consider thoughtfully and apply these principles consistently across the organization’s entire cloud estate or ecosystem. This application will often require tough decisions, and while success is unlikely to be found in their uneven or incomplete application, we ought to acknowledge that budgetary, technological, organizational, and even political constraints are likely to prevent purity on most organization’s journey transitioning to a complete EOA. But that’s okay. As you will see, a cloud ecosystem evolves over time. It is not a big bang that happens the night you go live.

Principle of Platform First

Principle of Composability

Principle of Evolution

Principle of Restraint

Principle of Artistry

Principle of Following the Money

1. Principle of Platform First

The core platform elements must come first, even though it makes the first workload expensive.

Imagine an organization that has spent years in a hybrid cloud and on-premises situation. Perhaps there’s an aging on-premise enterprise resource planning (ERP) solution in place to manage the finances, an even older human resources system (HRS) that bedevils the HR division and colleagues alike, and “customer relationship management” (CRM) functions handled solely in Excel spreadsheets owned by individual teams and compiled to produce reports when the boss asks for them. Now, an upcoming modernization program that you’ve been budgeting for two years calls for moving that ERP to a modern, cloud-based solution. The “old way of doing things” would be to stand up the minimal cloud infrastructure (could be IaaS, SaaS, PaaS; the particulars don’t matter right now) required to support the new HRS, develop and deploy the workload, and call it a day.

But implementing a workload before you’ve built the core platform services on which the workload (and those that follow) relies is like buying an expensive living room set before you have a home to put it in. Yet, despite this obvious analogy, organization after organization—and consultancy after consultancy with which they partner—have a nasty habit of skipping the foundation, skipping the home construction, and going straight for the living room set.

Our Principle of Platform First calls on us to acknowledge that EOA often means higher up-front costs followed by dramatically reduced costs for future workloads. This is because the early workloads are often built in parallel to the cost of building the ecosystem that, once built, offers “composable” components that are reused again and again. EOA is designed to be open and transparent, allowing organizations to actively participate in its development. Its modular nature means it can be tailored to fit specific needs, and most importantly, it empowers organizations by giving them control over their technology, rather than having technology imposed on them.

Ensure that you allocate your “year one” budget accordingly, so that you don’t spend so much on the sofa and lamp—your ERP, HRS, CRM, etc. workloads—that you neglect the core platform, integration, and data distribution services that drive the most value from your ecosystem in the long-run.

2. Principle of Composability

The whole ecosystem is greater than the sum of its parts. Modularize workloads to be added or removed with little impact to the whole.

Gartner popularized the idea of composability—that is, “creating an organization made from interchangeable building blocks” (Gartner) —several years ago.

I wrote earlier how former eras of IT were filled with examples of architectures that placed mammoth ERP solutions in the center of the estate, and treated any further workload as an extension of that ERP system.

Composability calls on us to invert this thinking, beginning instead with core platform services, integration, and data distribution and placing those services at the center or our ecosystems. ERP then becomes a node, albeit an important node, just a collection of workloads alongside any other core business system.

I could have called this the Principle of Keeping the Core Clean, wherein we implement core business systems such as ERP with as little customization as possible, let it do its thing, certainly do not try to shoehorn in functions for which it was not designed, and then build composable solutions using mastered and integrated data to meet the organization’s more unique needs.

EOA requires us to modularize individual workloads so that they are, individually, more flexible, more easily customized, and even retired when no longer needed, then assembled in such a way where the organization relies on the ecosystem as a whole to do its heavy lifting, rather than on a handful of monolithic apps.

3. Principle of Evolution

The ecosystem need not be fully functional on day one to be viable. Avoid lengthy “analysis”, do what you must to get started, then go from there.

How many times have you seen a public sector agency spend years getting ready to build something—scoping out an immense technology initiative, gathering requirements, researching possible solutions, budgeting, requesting proposals, awarding contracts— only to realize that the thing everyone thought was needed three years ago is no longer f it for purpose?

The Principle of Evolution suggests that we allow the ecosystem to evolve with the organization’s needs (and its budget), rather than mapping out every minute detail of many specific workloads. We’re not advocating unchecked experimentation here, rather that we guide the ecosystem’s evolution with principles and desired outcomes rather than years’ worth of accumulated requirements.

This principle is like that of the “minimum viable product” (MVP), which has been floating around for many years. Swap “platform” in place of “product” and you have the idea. Too often architects, particularly those grounded in the art of implementing big point solutions, get hung up with the inner workings of core business systems and fail to see the forest for the trees. Months or even years are spent discovering, analyzing, designing every bit of minutiae functionality associated to specific workloads.

Evolution challenges us to first build the core platform services required across the ecosystem, deploying alongside this one or a handful of workloads that strike a good balance of providing value to the organization but without being so complex that they take years to deploy. Then go from there.

You may be tempted to think that this is a too big of a change for the Public Sector, but the secure, risk-reducing quality of this approach says otherwise.

4. Principle of Restraint

Not all data or application functionality is needed everywhere or in real-time. Be discerning between what you could do and what is needed.

If I have a dollar (or a euro, pound, franc, etc.) for every time someone has insisted to me that something simply had to be real-time…

Many will have worked with architects who lack this restraint. When given a choice between technologies, they’ll always choose the one with the most features, the newest technology, the data insights produced in real-time, etc. This reflects point solution architecture and task-based thinking where the purview of the architect ends at the bounds of their own solution. But it is antithetical to EOA where the results of a system based ecosystem working as one is far more important than the task-based outcome of any single workload.

Let’s briefly consider that common scenario of real-time data analytics. Many organizations struggle with data latency in legacy analytical workloads, but when pulling back the curtain here, we find that we’re talking about days between data collection and data visualization. Building a data platform that reduces this latency to hours is sufficient, simpler, and cheaper in many cases. In other words, if we can improve data latency from days to hours, is real-time truly necessary? It may be, but you are wise to take the decision thoughtfully before committing to often more costly real-time integration.

The principle of restraint challenges us to discern the difference between what we could do and what is actually needed in the context of the ecosystem and the business need.

5. Principle of Artistry

Many ecosystems look alike in their common elements. Artistry is in how these are combined in practical terms for the organization and industry.

The principle of artistry was not obvious until after our notional “Reference Ecosystem”, which we will discuss later, had been applied to various organizations across different industries. “Ecosystem maps”, as we call them, looked very different in the early days of my work with EOA. Over time, as the Reference Ecosystem improved, however, I began to see ecosystems looking more and more like the composite.

I have found that cloud ecosystems across individual organizations share much in common. Nearly all of them are built with some selection of the same core platform services such as Microsoft Purview for data governance, lineage, cataloging, etc. Nearly all of them contain some combination of event, logic, and batch integration services. And most organizations rely on the same set of core business systems.

The ”artistry”, therefor, is in combining and prioritizing these technologies to support different aspirations and to achieve different outcomes. For example, a regulatory body may be tracking the organizations it regulates and any enforcement actions, a court system is preoccupied with managing its case backlog, military and defense organizations are concerned with the people and supplies deployed to far-flung places, law enforcement will prioritize completing duty rosters without burning out their force, national security and intelligence is focused on communicating threats quickly and to the right parties, local government (or “councils” in some regions) need to be careful in planning and costing their work, healthcare institutions must generate and prioritize clinical care needs.

These are, of course, very different problems to solve. However, by rigorously applying the principles of EOA, focusing on data with composable applications built atop that data, and avoiding one-size-fits-all monolithic point solutions we can inject the “artistry” into combining various technologies to produce the fit-for-purpose solutions that are needed.

The principle of artistry challenges ecosystem architects to use similar paint colors (the underlying technical services) to paint ecosystems that match the mood of their organization’s aspirations and desired outcomes.

6. Principle of Following the Money

Technology vendors like Microsoft focus their investments on what they believe are the technical capabilities of the future. Hitch your wagon to these.

We’re not talking about broad technology categories such as “AI”, “data platform”, or “low code” (a phrase that I abhor). No, the principle of following the money leads you to very specific technologies with which you should be building your cloud ecosystem.

EOA really began to ignite as a concept in 2023, which happens to be the year in which Microsoft announced its “Fabric” data platform capabilities. This proved a perfect example of the Principle of Following the Money, wherein one was able to place bets in the form of investment and upskilling on technologies where Microsoft was itself investing. At the time of writing, Microsoft technologies such as Fabric, AI Search, and Dataverse were the recipients of significant investment, which in turn leads to the conclusion that these are ideal technologies upon which ecosystem architects can rely for the foreseeable future.

Perhaps a better example from this era is Microsoft Purview, which, while lacking the marketing investment that Microsoft has made in technologies like Fabric and Power Platform, has nonetheless quietly become Microsoft’s one-stop-shop for data governance.

“ In the public sector, robust governance, clear data lineage, and tools like Microsoft Purview are essential for ensuring transparency, compliance, and accountability.

Governance frameworks help manage data access and usage, while data lineage provides a clear view of where data comes from, how it’s transformed, and where it’s used, ensuring data integrity and trust. Microsoft Purview adds an extra layer by offering comprehensive data cataloging and tracking capabilities, which are crucial for maintaining oversight and control in highly regulated environments, ultimately helping public sector organizations meet their compliance and security obligations.”

Though it is impossible to guarantee that any technology will live forever—because no technology really will, at least not in its current form—the principle of following the money suggests that we are best served to learn and construct future-ready cloud ecosystems that rely on technologies where Microsoft (or your preferred cloud technology vendor) is investing heavily today.

Reference Ecosystem

I mentioned the “Reference Ecosystem” when earlier discussing the Principle of Artistry. We’ll discuss this in more detail below. Let’s nail down some key terms here so that we’re clear on the difference between them:

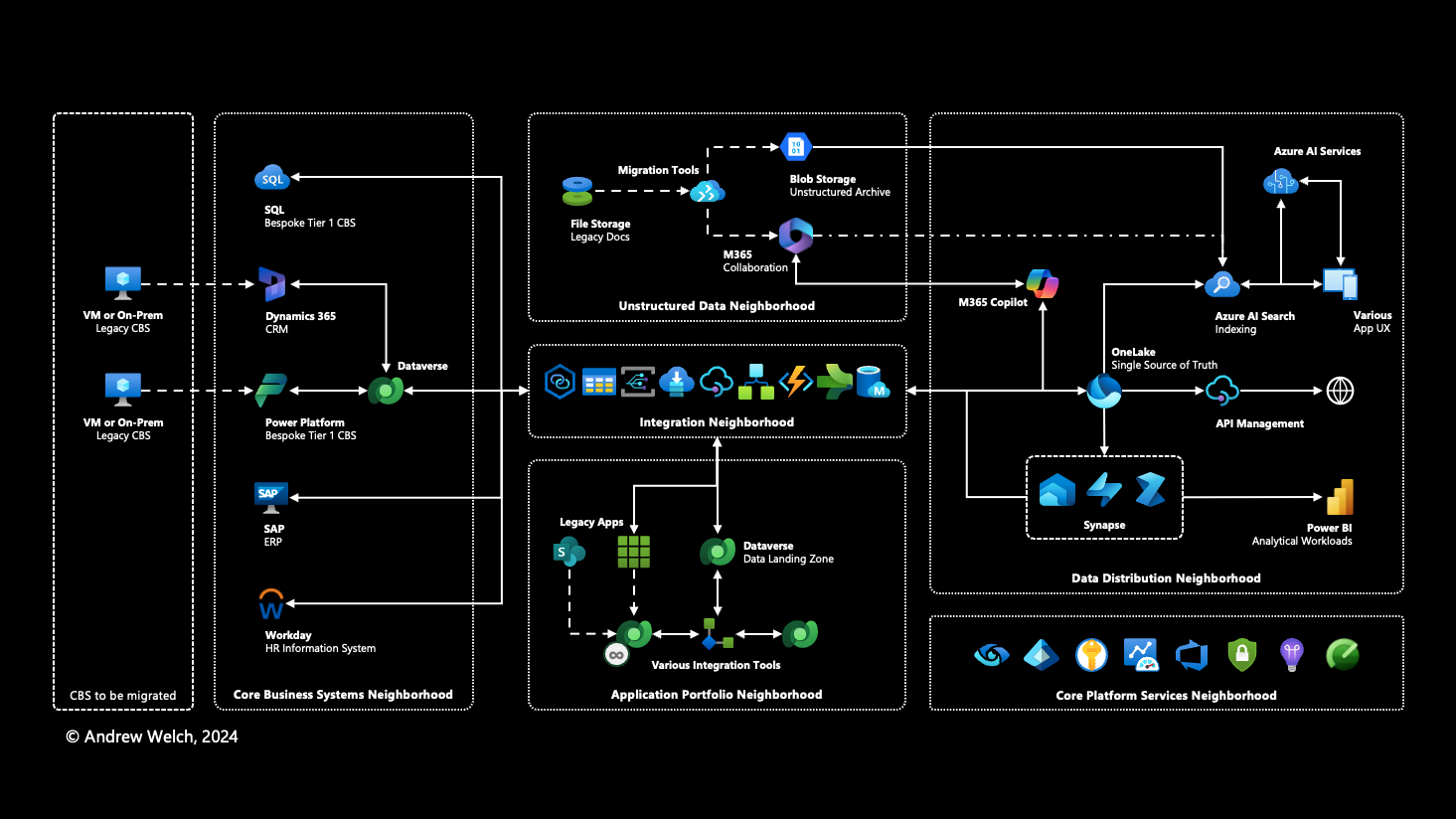

An Ecosystem Map is a high-level architectural diagram of an organization’s cloud ecosystem, and something that every organization must create at the start and continuously evolve as they progress on their journey;

The Reference Ecosystem is a specific ecosystem map that my team and I have created as a composite of many different cloud ecosystems across many different industries.

The “map” metaphor is instructive here. It is used to distinguish an ecosystem map from the various forms of architectural diagrams, nearly all of which tend to include more technical minutiae than a typical ecosystem map. Whereas an architectural diagram provides specific parameters for specific technical solutions, an ecosystem map presents a higher-level, more visionary view of an organization’s cloud ecosystem.

To make an analogy to architecture in the physical world:

Solution architecture provides schematics—floor plan, dimensions, electrical wiring, ventilation, plumbing—from which a building is constructed;

Enterprise architecture provides plans for specific neighborhoods or systems such as a subway or electrical grid;

Ecosystem architecture and, by extension, an ecosystem map shows us the entire city.

This analogy is fundamental to understanding and practicing EOA. Thinking of an organization’s cloud ecosystem as a city, we then conceptualize the next-level-down component parts of the ecosystem as “neighborhoods” (we might have also called them “boroughs”). Cities the world over are pieced together this way: Downtown, Seaport, Southie, etc. in Boston; Greenwich, Soho, Canary Wharf, etc. in London (though you’re forgiven if you thought I was talking about New York until you got to “Canary Wharf”); Palermo, Recoleta, Puerto Madero, etc. in Buenos Aires; Norrmalm, Gamla Stan, Kungsholmen, etc. in Stockholm. The list goes on.

Each of these neighborhoods share the quality of dividing their city into smaller pieces, each often with their own distinct culture, aesthetic, or purpose.

My team applied this same concept to EOA, clustering technologies and workloads devoted to similar purposes into distinct neighborhoods, and tying them together with the flow of data, logic, and actions—our roads, subway lines, waterworks, electricity, etc.—to build coherent cities in the cloud.

To do this, we compared the cloud ecosystems across real-world organizations in different industries and geographies to compile their common features and best practices. We then produced the “Reference Ecosystem”, that is to say, a notional cloud ecosystem that is a composite of the cases we considered. This reference ecosystem is the ideal standard, the prototypical notion of what a cloud ecosystem might look like.

Variation surely exists amongst individual organizations and sizes, industries, geographies, and other considerations such as regulatory requirements. To compensate for this variation, we then spent nearly two years applying our reference ecosystem to real-world scenarios, testing the composite model against actual guiding principles, business objectives, and requirements. We incorporated lessons learned from these scenarios to improve and refine the Reference Ecosystem over time, and were pleased to see how durable the model really is. Indeed, over time more and more of the ecosystems we mapped began to converge on and look more like our best practice Reference Ecosystem. We interpret this as evidence of its durability and flexibility to meet the needs of various organizational profiles.

In general, we found that most ecosystems are home to six major neighborhoods.

Core Platform Services, including many of the infrastructure, security, governance, management, and monitoring services used across the ecosystem. Largely synonymous with a “cloud landing zone”, the Reference Ecosystem above shows (left to right) Purview, Entra ID (formerly Azure Active Directory), Key Vaults, Azure Monitor, Notification Hubs, Security Center, Application Insights, and Power Platform Managed Environments as examples.

Integration, including services for (left to right in the diagram) technology-specific integration services such as OneLake shortcuts in Microsoft Fabric and virtual tables in Microsoft Dataverse, event-driven integration services such as Event Grid and Service Bus, use of APIs via API Management, logic-driven integration such as Logic Apps and Azure Functions, batch integration relying on Azure Data Factory, and a generic master data management (MDM) solution.

Core Business Systems, including the “Tier 1” business applications common in many organizations such as ERP, CRM, HRMS, etc. The Reference Ecosystem uses custom applications built atop Azure SQL and Power Platform, CRM in Dynamics 365, ERP in SAP, and HR in Workday as illustrative examples of the many solutions organizations rely on in their core business systems neighborhood.

Application Portfolio, which may include “Tier 1” applications but often include solutions aimed at smaller audiences or more niche business processes of the Tier 2 (“business important) and Tier 3 (“productivity”) variety. EOA in the Microsoft context ought to rely heavily on Power Platform in the Application Portfolio Neighborhood, though as you see above, we also highly favor Power Platform for core business systems.

Unstructured Data, including documents, files, photos, videos, etc. often housed in legacy network file storage, SharePoint, or Azure Blob Storage. Many of the Microsoft 365 services will operate here, noting that we strongly recommend using SharePoint as a data service for the Tier 1 or Tier 2 workloads found in other neighborhoods.

Data Distribution, which provides for data consolidation in (for example) OneLake, and for all manner of “downstream” data distribution such as search, APIs, data warehousing, analytical workloads, and use in AI-driven scenarios. We’ve also decided to place Microsoft 365 Copilot in the Data Distribution neighborhood as it—like many other scenario-specific Copilots that also reside there—relies on consuming, interpreting, and otherwise distributing data in response to user prompts. Note that M365 Copilot is hydrated with data from Microsoft 365 via the Microsoft Graph, and may be configured to consume data from elsewhere in the data estate, as well.

Navigate to your next chapter…